The bridge where friends meet

The Benson Street Bridge, or “Rainbow Bridge”, marks the city limit between Reading and Lockland, Ohio. Residents are fond of mentioning a sign that hangs over the bridge, proclaiming both Cincinnati suburbs to be “Where Friends Meet”. But if you talk to enough people from the surrounding area, you eventually hear whispers about a less friendly sign that used to be posted at the city limit, warning nonwhites not to set foot in Reading. My mother used to ride the bus with an African American person who still avoided that town, even though she said the whites-only sign hadn’t been up since the 1960s. You can imagine there must’ve been robust enforcement of that policy for it to have wound up on a welcome sign in the first place.

I first heard about her experience while growing up on the other side of town in Loveland. I was still too young and sheltered to take notice of the occasional weird remark or special treatment that in hindsight was almost certainly related to my ethnicity. But that story struck me, because we previously lived in Reading and we went to church and shopped there for several years after. To a child like me, Reading seemed like a perfectly normal community, not the sort of place that only a generation earlier might’ve treated nonwhites like criminals or kept us out.

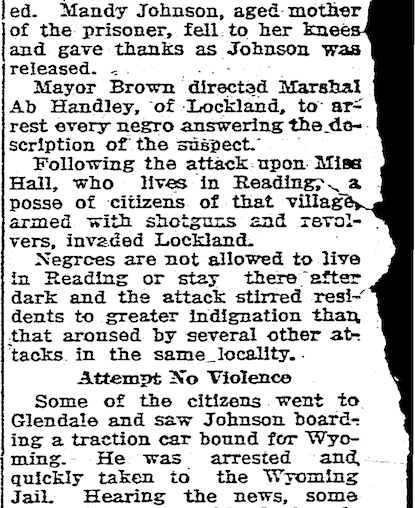

Reading’s decades-long history as a sundown town goes unmentioned in official town histories. A 1951 book commemorating Reading’s centennial tells some tall tales about Reading’s history but omits any mention of the ban on blacks. Surrounding the mayor’s embellished historical account are advertisements by local businesses praising Reading as a “progressive town”. In fact, it took me many hours of scouring local newspaper archives before I finally found a single published confirmation of the ban, from 1912.

Even if the community felt little need to advertise its ban in the press, those who needed to know about it did get the message. Census records show a purely white Reading, extremely unusual for the area and for a town of its size. Until the 1970s, Reading’s black population was usually nonexistent and never broke two percent of the total population. By contrast, neighboring towns had plenty of black residents, especially Lincoln Heights, the first black-led municipality in the North.

| Census | 1860 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 1,225 | 1,575 | ? | ? | 3,076 | 3,985 | 4,463 | 5,664 | 6,079 | 7,833 | 12,816 | 14,213 | 12,563 | 11,755 | 10,579 | 9,251 |

| African-American | 5 | 0 | ? | ? | 0 | 0 | 77 | 59 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 60 | 196 | 172 | 361 | 756 | Other | 0 | 0 | ? | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 15 | 30 | 84 | 111 | 352 | 378 |

| Total | 1,230 | 1,575 | 2,680 | ? | 3,076 | 3,985 | 4,540 | 5,723 | 6,079 | 7,836 | 12,832 | 14,303 | 12,843 | 12,038 | 11,292 | 10,385 |

Other communities have had their ugly side too. Loveland was where the KKK held regional conventions and staged photo-ops in the 1960s and 1970s. As recently as the 1990s, when I lived there, they almost put up their cross in front of City Hall, after Cincinnati put an end to their annual rallies downtown. Yet despite the problems African Americans in Loveland may have faced, they were still able to reside there in greater numbers. Reading’s demographics stood apart from its neighbors, a fact that was surely clearer in person than in a federal census report. The sundown town phenomenon was especially pernicious because it was, in a sense, uncontroversial in communities like Reading.

As I continued to search newspaper archives for additional information about Reading’s race relations, I stumbled upon articles about dozens of other towns across the country that had driven out their black residents, either violently or by threat of violence, and become sundown towns. Each time, I edited the town's Wikipedia article to acknowledge the town’s former antagonism towards blacks. In at least one instance, I found that a passage on race relations had already been added to the article, only to be removed by a local resident who perceived it to be “playing the race card”, or blowing out of proportion what was historically a fact of life. But this is not a case of judging yesterday’s norms by today’s morals. Back then, southern Democratic newspapers often mocked northerners and Republicans as hypocrites for criticizing Jim Crow laws but, on the other hand, implementing an extreme form of segregation not often found in the South. Some northern papers also noted the existence of sundown towns with regret. People knew it was wrong.

By now, such policies have been swept under the rug so thoroughly that many current residents are legitimately unaware of their hometown’s sordid past. For them, seeing it suddenly appear in the town’s Wikipedia article can feel like an attack on their own character. But silence can only perpetuate injustice. There’s at least one person who still bears the burden of that long-gone sign at the Reading city limit. She will continue to experience that stigma until the community acknowledges its past and declares a definitive end to institutional racism as publicly as it started. Mentioning sundown towns in these Wikipedia articles is the least I can do to start much-needed dialogue before it’s too late to give people like her some closure.

TrackBacks

TrackBack URL: <http://panel.1ec5.org/mt/mt-ping.fcgi/1705>

Comments

-

I saw that Reading, Ohio, was a sundown town on Wikipedia and decided to look further; I was wondering why there wasn't any more information. I am not from a family with decades of history here, I moved here back in 2021. We had a local history day in our history classes for the Junior and Senior High. It didn't mention any of this in any capacity. Thanks for your hard work! I hope more is added to the Wikipedia soon.

6/ 6/2020 @ 11:28 PM

Minh’s Notes

The main course

Who am I to comment on the terrible things that keep happening in this country? Me, I’m just someone who’s lived a sampler platter of a life.